Discover Tree Point Lighthouse

Beacon of History

Explore the rich maritime history of Alaska through the lens of Tree Point Lighthouse, a symbol of resilience and guidance for seafarers.

Historical Image Gallery

The Legacy of Tree Point Lighthouse

A fitting name for almost any protuberance along the coast of Southeast Alaska, as most of this area is part of Tongass National Forest, a temperate northern rain forest. There are, however, several gnarled, dead trees evident in the most recent twentieth century photographs. …Makes one wonder if perhaps these white, weathered giants were once used as a navigational reference and gave rise to the point’s name.

Although this theory on the origin of the point’s name makes a good story, more likely than not the dead trees are simply byproducts of logging. By January 4th, 1901, 679 Acres were set aside for the lighthouse reservation by executive order.

There were several reasons that convinced coastal surveyors Tree Point was a prime spot for navigational aids. Among them were:

1) There is a straight route from Tree Point to the open Pacific Ocean via Dixon Entrance

2) Situated seven miles north of the Canadian border, Tree Point is located along the Inside Passage roughly midway between the two largest cities in the area: Ketchikan, Alaska and Prince Rupert, British Columbia.

From Design to Construction

The Lighthouse Board approved the construction of Tree Point Lighthouse on April 24, 1903, and just over a year later, the light was activated on April 30, 1904. The lighthouse was the first, and only lighthouse, to be built on mainland Alaska. Two weeks after its debut, a small fire damaged the lighthouse, taking it out of service for a brief period before repairs were made.

The design of the lighthouse was similar to Mary Island Lighthouse, its neighbor to the north, that was completed a year earlier. The ground floor of the octagonal structure housed the fog signal equipment, which was connected to two horns protruding seaward from the western side of the lighthouse. Above the pyramidal roof of the first story, an octagonal tower extended upwards to a height of roughly sixty feet. The lantern room housed a third-order Fresnel lens, which produced a fixed-white light. On October 1, 1906, a red sector was added to the light to alert mariners of dangerous Lord Rocks. To store fuel for the lamp, two oil houses were constructed at distances of 50 and 100 feet southeast of the lighthouse.

Life at the isolated station was evidently difficult at times, as on December 21, 1931, Ketchikan’s paper reported: “the lighthouse tender Columbine came in from Tree Point light yesterday bringing in the keeper who had run out of supplies and was gorging himself on mountain scenery and boiled discouragement.”

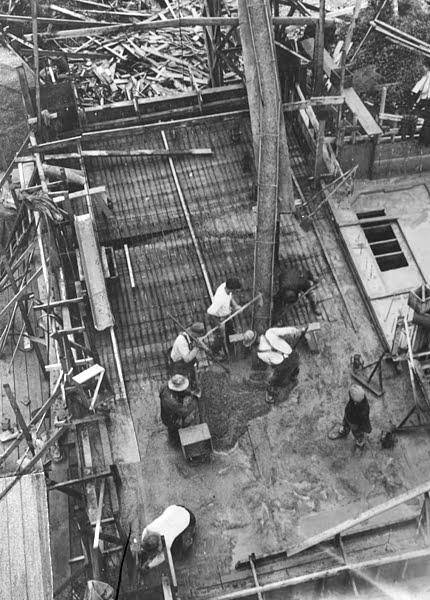

Although the lighthouse at Mary Island preceded the one at Tree Point, the lighthouse would be replaced by a reinforced concrete tower three years before the same change was applied to Mary Island. Work on Tree Point’s second tower began in November 1933 with excavation for the structure. The new art deco lighthouse, built of poured concrete, was situated just south of the original lighthouse, and a wooden trestle was built between the two towers allowing the original lantern room to be slid horizontally to its new home. The new lighthouse, finished in 1935 at a cost of $47,481, consisted of a one-story, eighteen by thirty-six foot building attached to a thirteen-foot-square tower that rose to a height of fifty-eight feet.

Under the supervision of Assistant District Superintendent Dwight W. Chase, Edward W. Laird designed the second Tree Point Lighthouse, along with five similar structures that replaced dilapidated, wooden lighthouses in Alaska between 1931 and 1940.

The following description of Tree Point Lighthouse appears in its registration form for the National Register of Historic Places:

The design and massing of the exterior are elegantly simple and symmetrical. Pilasters on the tower and fog-signal building form the dominant features that define the Art Deco style. The corners of both the tower and the single-story building are marked with 3-foot-wide faces that project above the lantern house gallery and parapets, respectively. Each is topped with a stepped-back cap at 2’3″ to the main face. Incised 3-foot by 3-inch vertical relief elements near the top of each pilaster reinforces the verticality. The corners of the tower project beyond the gallery to form the outward posts for an iron railing balustrade.

Illuminating History

A revolving, fourth-order Henry-Lepaute lens, originally installed in the old lighthouse sometime between 1913 and 1918, found its new home in the updated lighthouse on March 18, 1935. This lens, a marvel of its time, had served the old lighthouse faithfully, guiding countless sailors with its powerful beam.

In the original lighthouse, the lens relied on a twenty-seven-pound weight that needed to be wound up every three and a half hours to keep it revolving. However, advancements in technology allowed for significant improvements in the new lighthouse. With electricity provided by a Westinghouse generator, the lens’s movement was now powered by an electric drive motor, ensuring a more reliable and less labor-intensive operation. Additionally, the light source was upgraded from an incandescent oil vapor lamp to a more efficient 150-watt bulb, enhancing the lighthouse’s effectiveness.

The new lighthouse also boasted a modern fog signal system. This system, a type “F” two-tone diaphone, emitted sound through two horns extending from the lighthouse structure. This enhancement provided a crucial auditory signal to mariners navigating through foggy conditions, significantly improving safety and communication on the water.

Building Community for the Lights

The station had three six-room framed dwellings ad a schoolhouse that were located around the end of the tree-covered hill behind the tower, where they would be protected from the ocean winds. A narrow gage tramway and boardwalk ran 200 yards from the tower to the dwellings and then continued on for a quarter of a mile to the boathouse and hoisting boom, located on a small cove south of the lighthouse. To provide drinking water, a two-mile-long pipeline linked a large cistern near the dwellings to a lake in the nearby hills.

On September 4, a terse message was relayed to the radio station at Ketchikan by the Canadian radio station on Digby Island, near Prince Rupert, containing an urgent request that a boat be sent to Tree Point Light Station. The lighthouse tender Fern was in port and was directed to proceed to Tree Point. After getting under way, the operator of the Fern, learned through the Digby Island wireless station that the wife of the second assistant keeper was very ill and needed to be sent to Ketchikan for medical treatment as promptly as possible. The weather was stormy and the station power boat could not be used. The Fern was unable to land at the station but anchored for the night, and early the following morning the sea had subsided sufficiently so that the keeper’s wife was taken on board and taken to Ketchikan. The keepers at Tree Point were not furnished radio equipment, but the second assistant keeper had rigged up some apparatus of his own so that he was able to communicate with Digby Island station.

Don Anderson

Don Anderson

Don Anderson

In the 1930s, the Territory of Alaska provided a school teacher for the children at the station. Besides the three R’s, the students’ curriculum also consisted of learning to identify shells, sea life, and the constellations in the clear Alaskan skies. When the new lighthouse was being built at the station, the children performed puppet shows and plays for the workmen. To show their appreciation, the workers presented the young actors with hand-made toys and a walking life-sized mechanical man that emitted smoke and had blinking lights for its eyes.

When visibility at the station fell below one mile, the foghorn had to be activated. The station’s radio signal was synchronized to the two-tone blasts of the foghorn so that a captain could easily determine his distance from the lighthouse. Counting the number of seconds between receiving the radio signal and hearing the fog signal and dividing the time by five gave the distance in miles – just as counting the seconds between lightning and thunder can tell you how close you are to getting zapped.

In his autobiography, “Under Fortune’s Smile: Memories From America’s Half Century,” Don Anderson provides a humorous and candid account of his year-long sojourn at the station in 1954. Anderson’s mother speculated that his desire to serve at the isolated outpost had less to do with adventure seeking, as he maintained, than with self-doubt about his ability to manage “more normal circumstances.” His mother counseled him “to take up the challenge of joining others and even to sail the stormy seas than to seek out the safety of passive isolation.”

Conditions at the station, however, appear to have been far from normal. When the officer-in-charge (OIC) announced that he would no longer be taking his six-hour turn at the radio watches, an enraged subordinate spent the following night getting drunk on a bottle of whiskey he had smuggled to the station. The OIC put the fellow on report, but then had to lock himself in the lighthouse for safety as the madman bellowed taunts at him from the hill behind the tower and then “split the top panel of the lighthouse door with a broad head hunting arrow” shot from his seventy-pound lemon-wood hunting bow. The OIC radioed to Ketchikan for help, and a few hours later an investigation party, armed with a pistol and a rifle, arrived on an eighty-three footer.

Anderson escaped the sometimes monotonous life of a lighthouse keeper through the paperbacks that had accumulated (and remained mostly unopened) at the station. Hiking with a companion in the woods near the station was another diversion, but according to Anderson it “was slow going and never took us to anyplace that looked much different from where we had been all along.

Coast Guard personnel were removed from the station in 1969, when the beacon was automated, and in 1987, solar power units replaced the station’s generators. Two of the dwellings were razed in the early 1960s, forcing the four coastguardsmen to share a single dwelling. The Coast Guard signed a contract in 1974 for the demolition of all station improvements save the lighthouse, but when the contractor defaulted, Tree Point was left with the most intact light station in Alaska.

The revolving fourth-order Fresnel lens used in the lighthouse until 1963 along with a lamp are on display at the Tongass Historical Museum in Ketchikan. Although the lighthouse was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2004, the structure is in shockingly poor condition. All windows and doors (except those in the lantern room) are missing, exposing the tower’s interior to the harsh weather conditions that exist at the point. The remaining dwelling is also neglected; its interior in disarray. Part of the neglect is understandable giving the remoteness and inaccessibility of the station (the helicopter pad built in front of the lighthouse in 1966 was washed away by rough seas), but certainly some measures could be taken to weatherproof the lighthouse and retard further deterioration.

Click through the tabs for more information on Tree Point Lighthouse Keepers.

Jacob C. LaBryn (1904 – 1908)

Rolf Foosness (1908 – at least 1912)

George A. Lee (at least 1913 – 1915)

John C. Johnson (1915 – 1922)

Baard J. Lervick (1922 – 1923)

David O. Kinyon (1923 – 1925)

Mars P. Kinyon (1925 – 1928)

Frank W. Ross (1928 – 1930)

Ray I. Loney (1931 – 1937)

Sidney Elder (1937 – 1941)

Frank H. Story (1941 – 1942)

George R. Sprenger, Jr. (1962 – 1964)

Jack Andreasen (1964)

Otho O. Brown (1964 – 1965)

Vincent J. Palmer (1965 – 1966)

Robert K. McRea (1966 – 1967)

Dennis W. Harrington (1967 – 1968)

Roland G. Spencer (1968 – at least 1969)

Edward J. Lawrence (1904 – 1906)

Michael Ludescher (1906 – 1909)

Elmer J. Claboe (1909 – 1910)

Alphues Jewett (1910)

John C. Johnson (1910 – 1914)

Chart Pitt (1914)

Edward Pecor (1914 – 1915)

George F. West (1915 – 1918)

Baard J. Lervick (1918 – 1922)

Mars P. Kinyon (1922 – 1925)

Frank W. Ross (1925 – 1928)

Eugene E. Mead (1928 – 1929)

Ray I. Loney (1929 – 1930)

Arthur F. Frey (1930 – 1931)

Allan E. Johnson (1931 – 1934)

August Waltenberg (1934 – 1936)

Paul Strand (1937 – 1938)

Frank H. Story (1938 – 1941)

Charles B. Bohm (1904 – 1905)

Wilfred Monette (1905 – 1906)

James L. Brightman (1906)

Alfred Nelson (1906 – 1907)

Alphues Jewett (1907 – 1910)

John C. Johnson (1910)

Chart Pitt (1911 – 1914)

David O. Kinyon (1914 – 1915)

Odin B. Lokken (1915 – 1916)

William A. Shoemaker (1916 – 1917)

Baard J. Lervick (1917 – 1918)

David I. Harner (1918 – 1919)

Ellery A. Teeter (1919 – 1921)

John Erickson (1921)

Mars P. Kinyon (1921 – 1922)

Glenn E. Maddox (1923 – 1924)

Frank W. Ross (1924 – 1925)

Paul Strand (at least 1929 – 1930)

Arthur F. Frey (1930)

Angus Graham (1930 – 1932)

August Waltenberg (1932 – 1934)

Joseph S. Washburn (1934 – 1937)

Frank H. Story (1937 – 1938)

Paul Schuttpelz, Jr. (1938 – 1940)

Willie M. Perryman (1940 – 1944)

Howard G. Holcomb (1962 – 1963)

Michael P. Joyce (1962 – 1963)

R. Buswell (1962 – 1963)

Carl C. Cooper (1963 – 1964)

John W. Massey (1963 – 1964)

Daniel H. Sagaert (1963 – 1964)

Leon H. Moon (1964)

Lawrence A. Heite (1964 – 1965)

Robert D. Midgett (1964 – 1965)

Jimmy B. Standridge (1964 – 1965)

James L. Piver (1965 – 1966)

Frederick C. Reese (1965 – 1966)

Wayne D. Wedeman (1965 – 1966)

Thomas D. Knobe (1966 – 1967)

Luther D. Stidhem (1966 – 1967)

Richard S. Kroll (1966 – 1967)

John J. Gammell (1967)

Harry C. Baxley (1967 – 1968)

Ralph E. Perkins (1967 – 1968)

Claude D. Pendergraph (1967 – 1968)

W.R. Daulton, Jr. (1968 – 1969)

James Wilken (1968 – 1969)

G.R. Palmer (1968 – 1969)